What a day to be writing about inflation! Today’s headline CPI print of 9.1% scorched even the highest economic estimates and proved to Wall Street that inflation is neither forecastable nor stoppable. Even Biden is in disbelief, saying the data is out of date since gasoline prices have been falling for 30 days. I can’t say I predicted the higher than expected print, but I do have a feeling this print is going to leave a napalm run of destruction in its wake.

Over my vacation in Italy (during which eur/usd traded at parity, giving me a discount on my shopping), I finished the book The Great Inflation and Its Aftermath by Robert J. Samuelson. Samuelson was a journalist for the Washington Post, Newsweek, and the National Journal during the 70’s and 80’s. In his last op-ed in Oct 2021, he presciently warned against being complacent about inflation, and quoted Volcker: “Don’t let inflation get ingrained. Once that happens, there’s too much agony in stopping the momentum. That’s the lesson of central banking all over the world.” His book is an account of the inflationary period of the 70’s and 80’s and how it affected society, politics, and the world that came after.

Wall St economists have the best data and even they can’t forecast inflation with much accuracy. To me, history is the best roadmap for trading this current inflationary regime. These are some quotes from the book and takeaways on how lessons from the Great Inflation may apply to today.

The struggle to pinpoint where inflation came from:

pg 24: Well, what about the argument that high inflation was the unfortunate spillover of Vietnam and the successive surges of oil prices in 1973—74 and 1979—80? In this telling, inflation was not mainly a failure of government policy or economic theory. It was collateral damage from other events and, therefore, does not deserve much independent attention. Superficially, this seems possible. In the 1960s, it’s said, wartime spending created a classical inflationary hothouse: too much demand pressing on too little supply. Wages and prices rose. Later, the global oil cartel (OPEC, the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries) inflicted new damage. But these notions, though plausible, are easily disproved. If Vietnam had been the central cause of inflation, then inflation should have abated as the war wound down (that's what happened after the Korean War). It didn't. And if oil were the source, then energy should have been a major part of higher inflation. It wasn't.

Lesson: Today the market blames inflation on the war in Ukraine and covid supply shocks. Focusing on these factors may be missing the bigger story - that inflation is a social and psychological phenomenon that can continue well after these exogenous shocks fade.

What is at stake if we don’t get inflation down:

pg 30: Lenin is reputed to have said that the best way to destroy a capitalist society is to debauch its currency—indeed, it's probably the best way to destroy any society, because high inflation arrays a government against its citizens.

Lesson: Fighting inflation is an existential crisis for today’s economies. Countries that fail in defeating inflation will emerge weaker relative to those that don’t.

How even 6% unemployment won’t help:

pg 67: The idea of "gradualism" was that a slight economic slowdown and the resulting "slack" (unemployed workers, spare industrial capacity) would gradually reduce wage and prices pressures. Unemployment, which was 3.4 percent when Nixon moved into the White House, would rise to just above 4 percent—slightly more than "full employment." Competition among workers and companies for jobs and sales would curb inflation without a recession. Most Americans would hardly notice. Nixon's economists expected these good results in 1969 and 1970. What happened was different. In 1970, there was a mild recession. Unemployment reached 6 percent by December. Inflation barely diminished. It was 6.2 percent in 1969 and 5.6 percent in 1970.

Lesson: Unemployment in the US is 3.6% today, similar to 1971. A mild recession and UE moving up to 6% won’t be enough to get inflation sustainably lower.

How loosening too soon in response to economic weakness will result in a resurgence of inflation:

pg 79: When inflation inevitably worsened, the Fed reacted—acknowledging that it had left the highway—by tightening money and credit. Slowdowns or recessions (those of 1966, 1969—70 and 1973—75) ensued. But unfailingly, these responses were inadequate, because (as [Arthur] Burns noted) they were abandoned too quickly. Inflation abated briefly, and then the errors were repeated.

pg 103: The Federal Reserve had repeatedly relaxed its anti-inflationary policies prematurely. Companies and workers became conditioned to rising prices and wages in an advancing economy. So, once the economy recovered, inflation accelerated again, ultimately exceeding levels reached in the previous expansion. The pattern was well-established. From 1965 to 1966—a slowdown, not a recession—inflation retreated slightly, from 3.5 percent to 3 percent; but as the economy reaccelerated, inflation reached 6.2 percent by 1969. After the 1970 recession (and the imposition of wage-price controls in 1971), inflation dropped to 3.3 percent in 1971—and then zoomed to 12.3 percent by 1974. The next recession, ending in 19 75, reduced inflation to 4.9 percent in 1976—but it jumped to 13.3 percent in 1979.

Lesson: Current market pricing predicts rates will reach a peak of 3.6% by December and start cutting in response to a recession by Mar 2023. I believe the Fed has studied the lessons of history and will end up hiking rates higher and keep them there longer than the market thinks. Betting against rate cuts in 2023 could be a positive carry trade! It will be painful for the market and the economy though.

When Treasury term premium existed and yields trading above the rate of inflation:

pg 101: High inflation seemed too entrenched for mere mortals to conquer. It had become a staple of daily life. Economic sophisticates and ordinary people alike shared these views. In 1981, interest rates on 30-year Treasury bonds averaged about 13.5 percent; on 30-year fixed-rate mortgages, they were 15 percent. At those rates, bond investors were signaling that they had lost faith in the government's ability to control inflation. They were protecting themselves against future price increases of 10 percent a year or more. The high interest rates would cover the erosion of their original investment and provide an annual return of, say, 2 to 4 percent.

How gold and USD traded in response to a weakening of Fed credibility:

pg 112: Still, Volcker's regime started badly. In August, he convinced the Fed governors to raise the discount rate (the rate on Fed loans to commercial banks) and did so again in September. But the second vote was only 4-3, and the narrow margin was seen as proof that Volcker had already lost political control and couldn't undertake further anti-inflationary actions. Prices of metals—gold, copper, silver, platinum—rose sharply, as investors fled dollars that they expected to lose value. From early August to late September, gold prices increased from about $300 an ounce to nearly $450 and copper prices from about 90 cents an ounce to $ 1.20. In late September, Volcker flew to Belgrade in what was then Yugoslavia for the annual meetings of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, the major global economic agencies. There, he heard loud complaints from foreign countries about the dollar's plunging exchange rate: Investors were switching into other currencies whose value (they thought) would hold up better.

Lesson: During the 70s, gold experienced a huge bull market and USD weakened significantly. Today we are seeing the opposite, to many gold bugs’ frustration. I think one reason is that most central banks today are experiencing similar inflationary dynamics but are farther behind the curve than the Fed. Because the Fed has been the most proactive central bank in tightening, USD is rising against all other currencies, including precious metals.

Long end bonds have also been rallying despite higher CPI prints, which is the opposite of the 70’s. I believe the reason is that the market believes a recession will bring inflation down to reasonable levels and that the Fed will be forced to cut eventually. Long term inflation expectations are still low compared to the 70’s. This may change if the Fed gives up on fighting inflation and is forced to ease prematurely.

How bad the recession had to get to bring inflation down during the Volcker era, and the political backlash:

pg 101: Industrial production dropped 12 percent from mid-1981 until late 1982. In many industries, declines were steeper. In autos, it was 34 percent (from June 1981 to January 1982) and in steel it was 56 percent (from August 1981 to December 1982). By 1982, the number of business failures had tripled from 1979. Construction starts of new homes in 1982 were 40 percent below 19 79 levels. Worse, unemployment exploded. By late 1982, it was 10.8 percent, which remains a post—World War II record.

Gluts crushed the economy. There were surpluses of almost everything—workers, cars, office space, steel—with the glaring exception of credit. Business and labor had to respond to the unanticipated distress conditions. Facing lower profits, losses or bankruptcy, companies fired workers, cut wage increases and pressed for lower prices on everything they bought. Workers had to accept the reality that they could no longer command annual wage gains of 7, 8 or 10 percent. It was a buyers' market.

pg 107: The question remains why Reagan was so steadfast in his support. Volcker believed that public opinion had shifted. Americans' growing fears of runaway inflation made them more tolerant of the hardships necessary to suppress it. Though this was probably true, it could not be seen in Reagan's popularity ratings, which collapsed. Early in his presidency, Reagan's approval had reached a high of 68 percent in May 1981. By April 1982, it was 45 percent (46 percent disapproved); by January 1983, it was 35 percent, the low point (56 percent disapproved). Reagan was condemned as both heartless and headless…The deep tax cuts contributed to huge budget deficits, which in turn were blamed (along with the Fed) for high interest rates. Reagan was portrayed as spearheading an economic assault against ordinary Americans.

There was an outpouring of bills and resolutions to impeach Volcker, roll back interest rates or require the appointment of new Fed governors sympathetic to farmers, workers, consumers and small businesses. Representative Jack Kemp, a prominent Republican "supply-sider," wanted Volcker to resign. In August 1982, Senator Robert C. Byrd of West Virginia, the Democratic floor leader, introduced the Balanced Monetary Policy Act of 1982, which would have forced the Fed to reduce interest rates. It seemed possible that the Fed's liberal and conservative (mostly supply-sider) critics would coalesce in a grand coalition.

pg 117: Disturbingly, the recession was harsher than expected. The Fed's staff economists had expected a recovery by mid- 1982; so had many private economists. But it wasn't happening. Recalled Gramley: Early in the year, I was making speeches predicting an upturn in the economy in the second quarter [April—June], and when that didn't happen, I said by mid-year. By June and July, with each passing statistic, it became increasingly evident that the turnaround wasn't going to be there.... Our expectations were thoroughly disappointed. The gloom and doom was beginning to spread.

But arrayed against that was the fear that if the Fed relaxed too soon it would forfeit its claim to public belief that it would not tolerate higher inflation. It was "credibility" that, in turn, would purge inflationary psychology and re-create the self-regulating discipline that would restrain wage and price increases. If the Fed repeated previous errors, easing money and credit too soon, the whole gruesome episode might be in vain.

Lesson: Bringing inflation down from double digits requires a lot of pain to be taken by ordinary citizens. It’s also political suicide for the president and Fed chairman. Look around today and you’ll see that people are fine for the most part. Unless you’re in crypto or VC-funded startups, few are complaining about not being able to find a job. By the time the Fed is done battling inflation, the economic picture will be much grimmer.

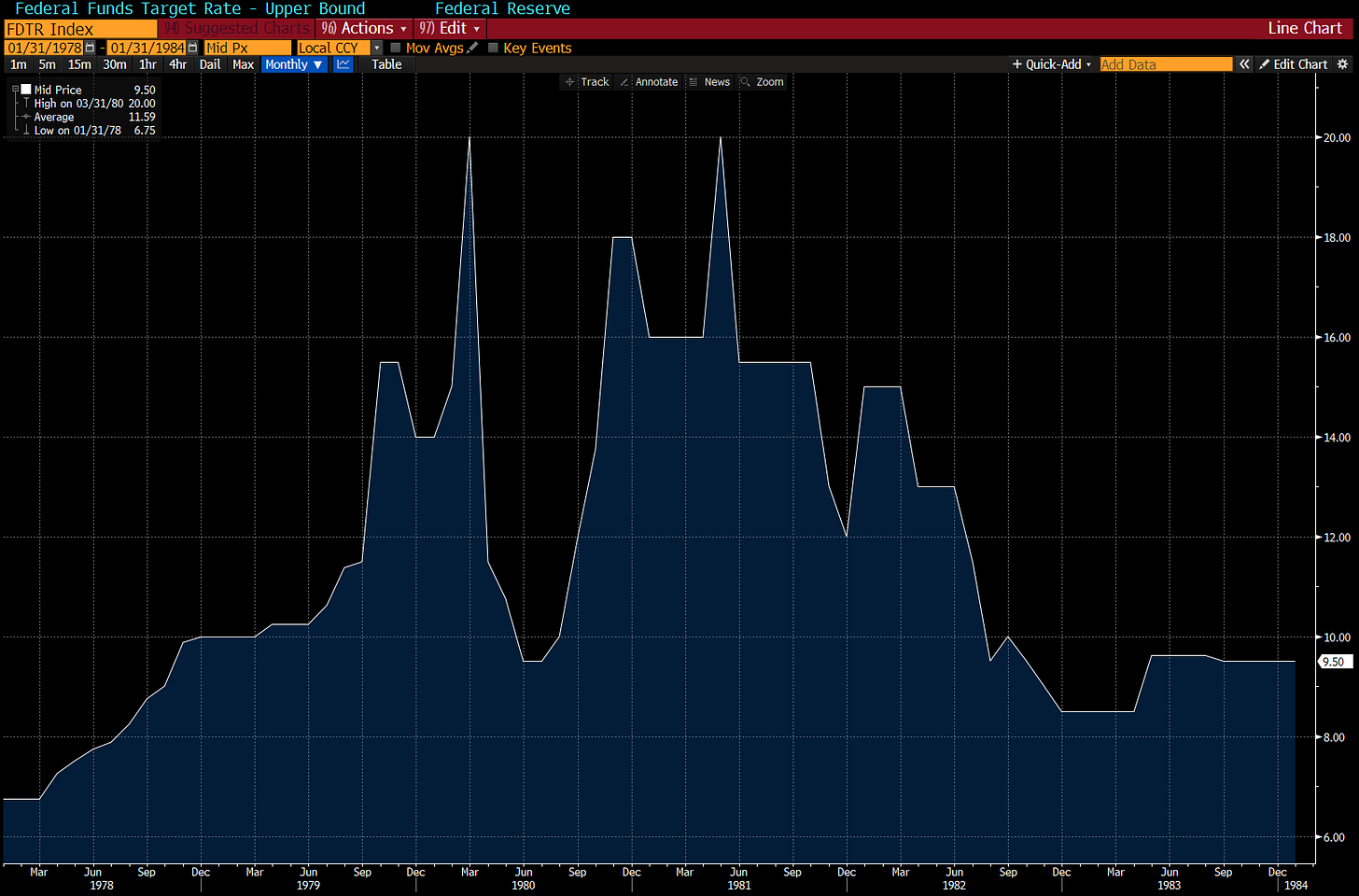

Contrary to what most people think, Volcker didn’t actively make the decision to crank rates up to the high teens. Due to political pressure, Volcker threw up his hands and let the market determine the interest rate in response to a fixed money supply. This is why a chart of Fed Funds is all jagged like this:

pg 110-114: Until October 1979, the Fed had targeted interest rates—namely, the Fed funds rate governing overnight loans between banks, the only market rate it controls directly. The Fed increases or decreases reserves until supply and demand produce the desired rate. What Volcker proposed was shifting the focus from interest rates to the basic money supply: cash plus checking accounts, known as M1. The Fed would no longer try to guess the "right" price for money. It would instead provide a given amount of bank reserves, which through subsequent borrowing and spending would translate into a given amount of money. If inflation was too much money chasing too few goods, squeezing the amount of money would squeeze inflation.

The new approach exempted Fed officials from having to make explicit and politically sensitive decisions on interest rates. Volcker also believed that the Fed no longer knew what "the right rate" might be, even in theory. Regulating the amount of bank reserves would allow rates to find their own level. If demand for loans and money was high, rates would rise, perhaps spectacularly. If not, they might fall. Once the Fed adopted its new approach, the Fed funds rate jumped immediately to 13.8 percent in October, up from 11.4 percent in September.

Lesson: The Fed needs to target the money supply, not just interest rates. Fortunately the Fed is doing that with QT. The question is whether QT is happening fast enough.

What a peak in inflation looks and feels like:

pg 120: Then, in succeeding weeks, the unexpected happened. The money-supply figures came in lower than expected. Interest rates dropped naturally. The given supply of bank reserves was more than adequate to support the existing money supply. The fierce bidding for overnight loans among banks (for Fed funds) so that banks could meet their reserve requirements subsided. Indeed, reserves might be increased—policy loosened—without breaching the money-supply targets.

On July 15 , the FOMC held a conference call. Most of the discussion was highly technical, focused on the official money-supply targets for the next year. By deciding not to reduce the targets, the Fed edged to an easier policy. As Volcker later explained:

It was sometime in July that the money supply suddenly came within our target band. The Mexican crisis was brewing. The economic recovery had not appeared. I thought, ahah, here's our chance to ease credibly.

Although the economy would not begin expanding again until early 1983, the Fed had relaxed its assault on inflation and committed itself to ending the recession. The country seemed to have turned the corner Volcker had so long sought. On July 19, the Fed cut its discount rate—the rate at which commercial banks could borrow from the Fed—from 12 percent to 11.5 percent, reflecting declines in the Fed funds rate.

By December, there would be six more discount rate cuts; these signaled that the Fed approved the decreases in market rates. On August 1 7, economist Henry Kaufman of the investment bank Salomon Brothers, long christened "Dr. Doom," predicted that interest rates would drop, a reversal of his previous position. The stock market responded with a 38.8 point increase in the Dow, then the largest one-day increase ever. Stocks rose about 50 percent in the next six months, as money came out of money market mutual funds and saving certificates and investors responded to lower interest rates and the prospect of economic recovery. By September, the money-supply figures had accelerated again, but Volcker stayed with his decision to ease. In October, the Fed officially demoted the significance of the money-supply figures, saying that they were too unpredictable to use as guide for daily policy. By December 1982, the increase in the CPI over the previous twelve months had dropped to 3.8 percent.

This concludes my book report. Despite all that was written, there is one glaring question - What could make today different from the 70’s and 80’s?

One has to caveat all of the above by acknowledging that today’s economy is pretty different from what it was like in the 70’s and 80’s. In 1980, US government debt to GDP was 31% vs 124% today. Treasury yields above 10% would make today’s government’s interest burden crippling. The economy is more sensitive to interest rates, as corporates and consumers are more levered to debt today. Labor is much less unionized than it was back then, although I would argue that today’s more fluid job market enables a wage-price spiral as much as a heavily unionized but sticky job market. The Fed also has the additional tool of QT, a more measured version of Volcker’s money-supply targeting. Perhaps these differences mean that interest rates don’t have to go up as much as they did during the Volcker era in order to reverse inflation. Or, the differences mean that the Fed will fail in reversing inflation, because the pain will be too difficult to bear. One thing remains clear- more pain, both in the markets and the real economy, needs to happen before we see inflation reverse sustainably lower.

Disclaimer:

The content of this blog is provided for informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as professional financial advice, investment recommendations, or a solicitation to buy or sell any securities or instruments.

The author of this blog is not a registered investment advisor, financial planner, or tax professional. The information presented on this blog is based on personal research and experience, and should not be considered as personalized investment advice. Any investment or trading decisions you make based on the content of this blog are at your own risk.

Past performance is not indicative of future results. All investments carry the risk of loss, and there is no guarantee that any trade or strategy discussed in this blog will be profitable or suitable for your specific situation. The author of this blog disclaims any and all liability relating to any actions taken or not taken based on the content of this blog. The author of this blog is not responsible for any losses, damages, or liabilities that may arise from the use or misuse of the information provided.